Android was designed from the outset as an industry collaboration, in the form of a partner-based ecosystem.

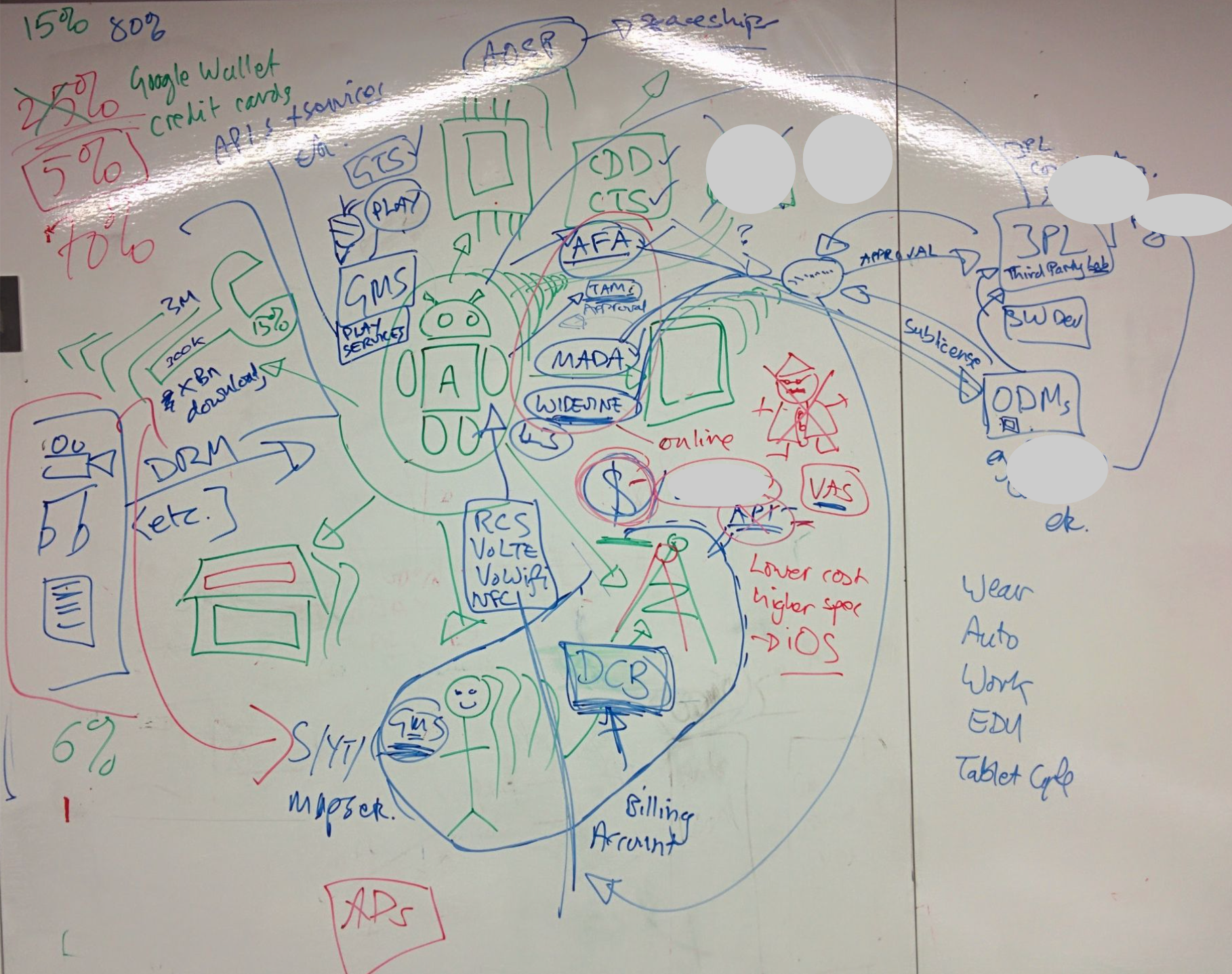

That ecosystem can be visualised like this:

Its purpose is to enable the mobile industry for the open Internet.

It has to align the interests and capabilities of:

- device manufacturers / brands

- mobile networks / operators / carriers

- semiconductor / silicon chip manufacturers

- app developers & content companies

- (including Google)

- retailers & distributors

- users / end customers

Before Android mobile experiences were highly fragmented between devices and networks. This was encouraged and proliferated by proprietary business models that required or accepted incompatible technology and inconsistent user experiences as a lever to capture users to a single provider.

This harmed product and service evolution and innovation, including Google's. Android was how Google intended to change that.

I negotiated hundreds of Google's Android partnerships from 2008 to 2015 and helped build a global partner ecosystem from the inside out.

Symbian had taught me what can go wrong when a platform fails to curate its ecosystem. Like Android, Symbian OS was a mobile computing platform built to enable devices to differentiate. But unlike Android, Symbian OS was produced by a software company owned by multiple competing hardware companies. The number of shareholders, and their expertise in hardware rather than software, were both death knells for Symbian as a company and Symbian OS as a technology.

One shareholder dominated, killing Symbian's technical and political independence, and eventually any ability to act as a platform rather than a component supplier. That shareholder was Nokia, who owned about 48% of Symbian's shares but whose products generated about 82% of Symbian's income, setting up an inbalance in Nokia's financial returns from Symbian that only encouraged it to further dominate its activities and compartmentalise it as a weapon against its rivals.

Without independence from its shareholders, Symbian OS was ruled by hardware businesses who thought of software as a component for the main product not the main product in itself. This happened at a time when the relative importance of software to hardware was fundamentally changing in the mobile industry, development of Symbian OS stalled and the whole enterprise was swamped by competitors.

When Apple and Android redefined the mobile experience Symbian was unable to respond. Every Symbian licensee switched to Android – or exited the mobile phone business altogether.

Success in balance

For Android we created the balance between its stakeholders that had been so sorely missing at Symbian. We achieved this by applying the same principles and boundaries to everyone, including Google. This was crucial, and one of the fundamental benefits of the way Android was managed as a project - as a dictatorship.

Andy Rubin, one of Android's co-founders and its leader, had learned through bitter experience in success and failure how to orchestrate technology partners to a single tune, even when at every moment they were poised to riff their own solos and rip the whole band apart. He wasn't alone in this understanding, but he led the Android group and our ecosystem of partners singularly for a decade. He was the conduit through which every strategic decision and action was made or not made. He ensured balance. Not perfection, but balance.

Principles define expectations.

Meeting expectations builds trust.

Trust encouraged our stakeholders to participate, while our principles left space for compliant differentiation.

Android principles

1. Complete

Android provides the fundamental software needed to build a compatible device.

2. Open

Everyone has full and equal access to all Android code & capabilities.

3. Free

Anyone can implement Android on any device without charge.

4. Compatible

Each Android version works the same way for every app on every compatible device.

Building 44, Android HQ at the Googleplex | Mountain View, California

photo credit: Tim Carter 2012

Boundaries define scope.

Boundaries define where stakeholders are subject to and must maintain the principles (i.e. within the ecosystem) and where they are free to contradict or compete with the principles (i.e. beyond the ecosystem).

Stakeholders can compete with the ecosystem, but not to intentionally undermine it.

Android boundaries

1. Brand

Google will not use the ‘Android’ brand to compete with partners.

2. GMS

Google mobile services (‘GMS’) are not available to partners who produce incompatible Android devices.

3. Revenue share

Google will only share revenue from GMS on Android with partners who contribute significantly to the ecosystem through innovation, scale or other ways.

4. Freedom

Android will not prevent its partners from working on competing platforms.

A scrappier exposition of the Android partner ecosystem

photo credit: Tim Carter 2014

Using Android’s principles and boundaries we built a powerful and complete partner ecosystem that changed the world.

In return, all partners shared in the influence and outsized returns of the new paradigm.

Android Pins

photo credit: Tim Carter, 2015

The success of our ecosystem prevented mobile Internet access being controlled by exclusionary business models.

We acquired our first billion users in a little over 5 years.

In the process, Android enabled multiple industries to participate in the next stage of connected computing, including wearable devices, automotive and TVs.